AC: "This is now the most dangerous part of the trip..."

Length: 6:18

LARGE (73.9 MB) ----- SMALL (7.5 MB)

ANDERSON COOPER: Well, the testimony today was met by deep skepticism, both at home and here in Iraq.

A new CNN/Opinion Research poll shows that only 40 percent of people surveyed believe the surge is working. Fifty-four percent say it is not. Last month, 43 percent of people said they trusted General Petraeus to report what is going on. Fifty-three percent said they did not.

And, according to a poll done by three other news networks, six in 10 Iraqis say security has actually gotten worse since the surge.

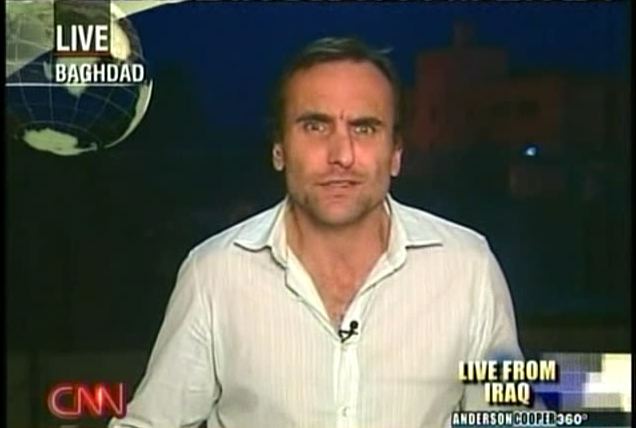

For some perspective, we are joined by CNN's Michael Ware and Michael Gordon of "The New York Times."

Michael Ware, the Bush White House has repeatedly said that al Qaeda in Iraq is the most significant enemy the U.S. is now facing. They have often portrayed the battle as a simple one, really, between America and al Qaeda terrorists. That message certainly seemed to contradict what -- or was contradicted by what General Petraeus said today.

MICHAEL WARE, CNN CORRESPONDENT: Yes, that is very true, Anderson.

Indeed, if you speak to commanders here on the ground, if you speak to senior diplomats here on the ground, whilst they acknowledge that al Qaeda remains at the forefront of some of the more clinical military operations, they admit, candidly, that the greater problem is Iranian influence, as they see it.

Indeed, as one top U.S. official said to me, the winner of the last six years is Iran. And, finally, members of the administration are waking up to that. And that is, indeed, reflected in the testimony today that Iran is the major problem now for the long term and, indeed, in the immediate term -- Anderson.

COOPER: Michael Gordon, General Petraeus said the military surge is basically meeting its military objectives. But wasn't the true objective of the surge originally to allow national political leaders, Iraqi leaders, time to reconcile? And that part has largely been a failure.

MICHAEL GORDON, CHIEF MILITARY CORRESPONDENT, "THE NEW YORK TIMES": Well, the purpose of the surge originally was to set the security conditions, as you point out, for political reconciliation. And they have made progress in reducing the levels of violence, by most objective measures.

But that is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the success of the surge. It is intended to enable a political solution. And that has yet to be accomplished.

COOPER: And why, Michael Gordon, is that so hard? Is it -- yeah, basically, why is it so hard for Iraqi political leaders to come to some sort of reconciliation, if all outside observers seem to be saying, that's the only way forward?

GORDON: Well, I think the Shiites have the upper hand in Baghdad, and I don't think they are inclined to relinquish control. They're deeply suspicious of the Sunnis. The Sunnis were disenfranchised in some of the previous elections, because they didn't participate.

But, you know, there is a positive element, which is the ground-up element, to work with the Sunni tribes and the former insurgents. So, the top-down part of the puzzle is not working out very well, but the bottom-up side of it is working better than anticipated.

COOPER: Michael Ware, Petraeus said that as many as 30,000 troops could leave by the beginning of next summer. It was sort of presented as though that was an operational decision.

In truth, it's really an operational necessity. The U.S. can't maintain these current troop levels, without putting even more strain on our already strained troops. Is that correct?

WARE: Yes, that is correct, Anderson. In fact, I'm struck by the way people are regarding General Petraeus' discussion of those troop levels until July of next year. People are acting like he has just announced some sort of phased withdrawal. Well, no, not at all. That was the timeline for the so-called surge from the beginning.

Indeed, it wasn't a surge. It was a one-year escalation of U.S. forces. And the clock was due to run out on that escalation in the summer of next year anyway. So, that is not a revelation at all.

COOPER: Michael Gordon, there has been a lot of argument over the statistics that General Petraeus is using. In 2006, the bipartisan Iraqi Study Group said that there had been -- and I quote -- "significant under-reporting of violence by the U.S. military" and pointed that -- quote -- "A murder of an Iraqi is not necessarily counted as an attack."

If that was happening back then, according to the Study Group, why should people believe the numbers that the military are using now?

GORDON: Well, people can dispute a given number or a given statistic, but a wide variety of trends point in the same direction.

For example, there's a non-governmental organization, Iraq Body Count, which is not necessarily friendly to the Bush administration, and they show a decline in August. Iraqi government data shows a decline. The Brookings Institution has an index which shows a decline.

What you really have to look at is the broad trends. But, you know, I don't think that is the key issue. If you put five combat brigades and 30,000 troops additional in Iraq, you will get a dampening of the violence. The key issue is, can this be sustained, as American troops are reduced over the next nine months, and can you drive the levels lower, because, while they're down, they're still high.

COOPER: Michael Gordon, you wrote a remarkable article in "The New York Times" Sunday magazine last week about the counterinsurgency efforts.

I want to ask you about the successes in Anbar. Can they be replicated in other parts of the country? I know it's already spreading somewhat. And are those successes, the reaching out to Sunni tribal leaders to turn against al Qaeda, is that related to the this called surge, or was that happening independent of it?

GORDON: Well, the answer is, really, it is a little of both.

The activity in Anbar was happening prior to the surge. And this was enlisting the support of the Sunni tribes against al Qaeda of Iraq. But it is spread to Baquba, where I was in June. I saw some of it firsthand. And that is directly related to the surge, because a lot of the residents were reluctant to take on al Qaeda until they saw an elevated and sustained presence of American forces.

And it's beginning to happen south of Baghdad in areas like Arab Jabour and Horajab (ph). And that, again, I think, is somewhat connected to the surge, because it is the additional level of forces that is giving some of the Sunnis down there the kind of courage and fortitude to take on al Qaeda.

COOPER: Michael Gordon, we appreciate your reporting, as always.

Michael Ware -- we are going to have more from Michael Ware when we come back. He has got an exclusive report from inside the Sunni insurgency that used to target Americans and now works with them, what Michael Gordon was just talking about.

Length: 7:06

LARGE (83.2 MB) ----- SMALL (8.3 MB)

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

LT. GEN. DAVID PETRAEUS, US ARMY: We can see that certain areas that were, in fact, sanctuaries for al Qaeda far beyond just Anbar Province, but also in areas south of Baghdad and north of Baghdad, Baquba and even areas now starting up the Tigris River Valley, are in fact no longer safe havens for al Qaeda.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ANDERSON COOPER: As we pointed out earlier, the success in getting Sunni tribes to turn against al Qaeda started in Al Anbar Province. And the change there has been dramatic.

CNN's Michael Ware got exclusive access to one of the reasons why. Take a look.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

MICHAEL WARE (voice-over): We are driving through Baghdad streets shortly after dawn. American-allied Sunni insurgents have agreed to smuggle us into Al Anbar Province, where just months ago, al Qaeda was in control.

(on camera): We are now beyond the capital, Baghdad, on the way to our linkup with the nationalist insurgents. To get this far, we've had to pretend to be Sunni and Shia as we pass through al Qaeda- controlled areas of the city and areas controlled by the Shia Mahdi militia.

(voice-over): Soon, an insurgent commander is guiding us along dirt roads bound for the small town of Zorba (ph), an al Qaeda headquarters for three years only recently overthrown.

Groups of gunmen in civilian clothes keep watch. The street is busy. Shops are open. A few months ago, it was not like this. Tribal elders once targeted by al Qaeda now move freely among the gunmen.

"There was no life here, because al Qaeda dominated the area," says this elder, Sheik Mohammed. "They were killing people. All the markets were closed."

Al Qaeda also slaughtered the town's policemen, but now the police chief coordinates with these gunmen. And, soon, many will join his ranks in uniform.

"Right here, in this place, al Qaeda hung people's heads from butcher's hooks," he says.

Though the tribes fought fierce battles with al Qaeda fighters, he says help from the government in Baghdad never came.

"The government doesn't exist here. It is against us, and against all of our operations in the area."

(on camera): What would have happened to me if I was here four months ago?

(voice-over): "Al Qaeda would have separated your head from your body," he answers.

That won't happen now, because of this man. His name is Abu Ahmed (ph). Behind the sheiks, the police officers and all the gunmen, he is the one in charge, a renowned guerrilla commander who led the fight against al Qaeda. It is his protection that is keeping us alive. We drive with him to see his recruits being trained at a remote U.S. Marine police training school.

It is clear he is well known, and it is his men being trained.

CORPORAL TIMOTHY COFFMAN, U.S. MARINE CORPS: We teach them a lot of our tactics. And we get them -- get them, you know, pretty damn -- pretty damn good.

WARE (on camera): Yes.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: We gave them weapons.

(CROSSTALK)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Give them weapons, uniforms.

WARE: We were at one of the checkpoints with the volunteer forces. What's the nature of those forces?

COFFMAN: Well, those are basically, like, local militia.

WARE (voice-over): The cooperation is paying off, says Coffman. Attacks here are dramatically down. Across Al Anbar, attacks used to peak at over 100 a week. They're now down to about seven. At checkpoints, Abu Ahmed's gunmen have fluorescent bands and identity cards from the Marines, plus banners, so U.S. aircraft don't strike them. It is a delicate accommodation.

"The insurgents will never stop until they liberate Iraq," Abu Ahmed says in front of the former al Qaeda headquarters. "We respect them, and, God willing, they will liberate Iraq. We are all against the occupation and for the establishment of a national Iraqi government."

Fears in Baghdad and in America of U.S. troops supporting armed groups opposed to the government are not unfounded.

Abu Ahmed insists that, "If our demands are not met by our petitions and by demonstration, then we will carry weapons and defend our Iraq."

But he can only defend us to the edge of his territory.

(on camera): Is this goodbye?

(voice-over): A reminder that al Qaeda is not far away, as we leave for Baghdad.

(on camera): This is now the most dangerous part of the trip...

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes.

WARE: ... going home, because we have been exposed here for a few hours. Al Qaeda could most likely know that we are here. And, without our insurgent escorts, this is the time they will strike.

What's wrong?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: There's a checkpoint.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: That's a checkpoint.

WARE: Oh. Hide the camera.

(voice-over): We make it through that checkpoint, leaving America's success story behind.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

COOPER: Amazing report there, Michael Ware, who joins us now from Baghdad.

Michael, I want to read you a question that columnist David Brooks asked in "The New York Times" last week. He said, "The crucial question now is, do these tribes represent proto-local governments, or are they simply regional bands arming themselves in anticipation of a cataclysmic civil war?"

What do you think the answer to that is?

WARE: Well, it's a little bit of both, Anderson.

Certainly, this is how, say, for example, western Al Anbar Province is being governed. It is from these tribes that come the chief of police, that come the local town major, and that eventually comes the provincial council. So, these are the fundamental building blocks of the local government.

At the same time, there is a flavor of warlordism about this. And that is what America is now harnessing, not just to attack al Qaeda, but to curb what U.S. military intelligence says is the heavy Iranian militia influence inside the central government.

COOPER: And are these tribal groups willing to work with the central government in Baghdad, the Shia- dominated government, and vice versa? Is the government of al-Maliki willing to work with these Sunni tribes?

WARE: The answer is no on both counts, Anderson.

These guys made it very clear to us on this day and on other days when I have contact with other groups, they are opposed to the Maliki government and any government that they believe is beholden to Iranian influence, a belief shared by many within the U.S. mission. So, these are anti-government forces that America is supporting against the government it created. And, certainly, within the Iraqi government, they believe that this is America building Sunni militias to act as a counterbalance to their influence -- Anderson.

COOPER: Fascinating developments. Michael Ware, appreciate the reporting.